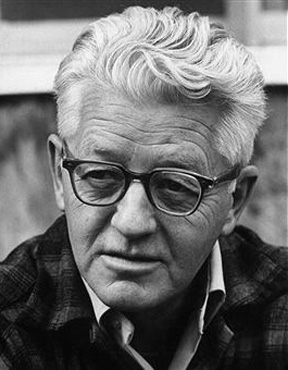

One of America’s great writers of both fiction and non-fiction, the late Wallace Stegner was a pioneer of the environmental movement starting in the 1950s. Stegner used his extraordinary literary gifts to wake Americans up about threats to the environment nobody was paying attention to.

One of America’s great writers of both fiction and non-fiction, the late Wallace Stegner was a pioneer of the environmental movement starting in the 1950s. Stegner used his extraordinary literary gifts to wake Americans up about threats to the environment nobody was paying attention to.

In 1960 Wallace Stegner published his personal manifesto on humanity’s need to preserve wild lands. March 1 this year is the 145th anniversary of America’s first national park, Yellowstone, in 1872. That law signed by President Ullyses S. Grant was the first of its kind and triggered the creation of national parks around the world. Today 100 countries have over 1200 parks or comparable land preserves. The United States now has over 400 parks covering 84 million acres in all 50 states.

To honor the historical significance of that March 1, 1872, law, and to remember again why these parks are so valuable, here is Wallace Stegner’s famous Wilderness Letter.

THE WILDERNESS LETTER From “Coda: Wilderness Letter,” copyright by Wallace Stegner, 1960.

Something will have gone out of us as a people if we ever let the remaining wilderness be destroyed; if we permit the last virgin forests to be turned into comic books and plastic cigarette cases; if we drive the few remaining members of the wild species into zoos or to extinction; if we pollute the last clean air and dirty the last clean streams and push our paved roads through the last of the silence, so that never again will Americans be free in their country from the noise, the exhausts, the stinks of human and automotive waste. And so that never again can we have the chance to see ourselves single, separate, vertical and individual in the world, part of the environment of trees and rocks and soil, brother to the animals, part of the natural world and competent to belong in it. Without any remaining wilderness we are committed wholly, without chance for even momentary reflection and rest, to a headlong drive into our technological termite-life, the Brave New World of a completely man-controlled environment. We need wilderness preserved– as much of it as is still left, and as many kinds– because it was the challenge against which our character as a people was formed. The reminder and the reassurance that it is still there is good for our spiritual health even if we never once in ten years set foot in it. It is good for us when we are young, because of the incomparable sanity it can bring briefly, as vacation and rest, into our insane lives. It is important to us when we are old simple because it is there–important, that is, simply as idea.